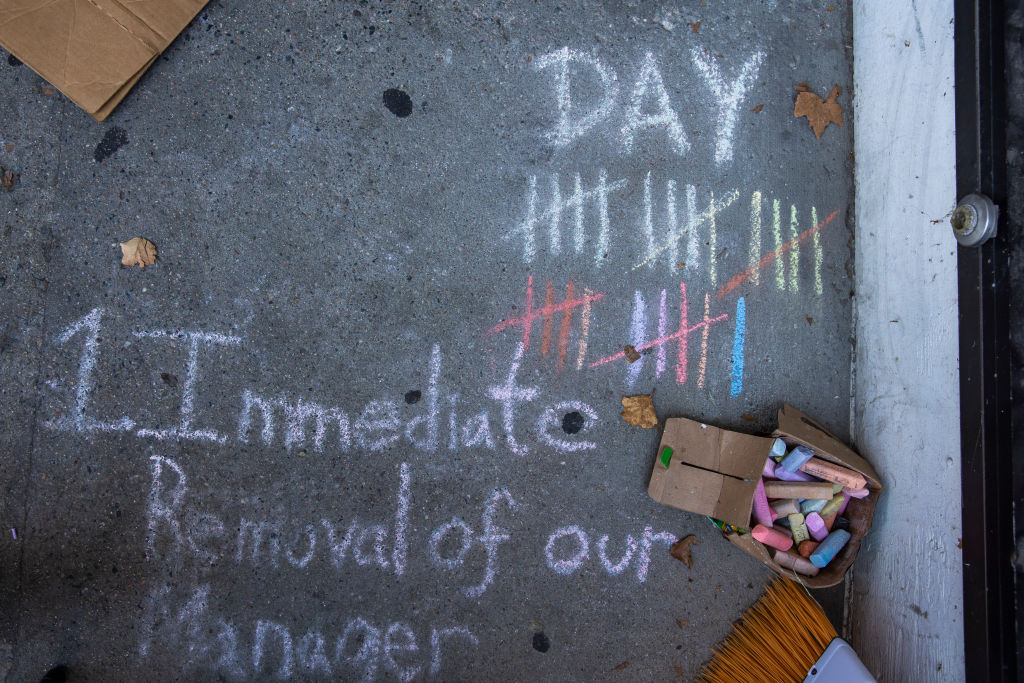

A year ago, a wave of workers—emboldened by a strong labor market and sick of feeling unappreciated—walked off their jobs, hastening what some in the media called Striketober.

Now, as more workers organize for better conditions, they’re finding that their bosses are pushing back, trying to convince workers to reject union overtures through means that violated the law, according to decisions by administrative law judges from the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB).

Employers have fired workers who were trying to organize unions, withheld pay and benefits from stores that were in the middle of organizing campaigns, and even spied on workers to find out who supported unions—all behavior that violates the National Labor Relations Act, according to recent decisions issued by the judges with the NLRB. There were 17,988 unfair labor practice charges filed with the NLRB in the fiscal year 2022 (Oct. 1 2021-Sept. 30 2022), a 19% increase from the same time last year, the NLRB said in a release on Oct. 6. That growth speaks to the increasingly charged nature of organizing drives; both unions and employers can file these charges.

Meanwhile, law firms and consulting groups are pitching their union-avoidance services in seminars, blog posts and podcasts that advise employers on how to “union-proof” their workplaces. “Events require a new diligence from employers who wish to remain union-free,” law firm Frost Brown Todd argued in a blog post earlier this year.

The employer response represents a no-holds-barred campaign to resist a wave of union victories that have swept across the U.S. over the past year with little historical precedent, including an organizing campaign by Starbucks Workers United that has won elections at 240 stores. Overall, there were 53% more union representation petitions filed in the fiscal year 2022 than in the previous year, according to NLRB data.Unions had a win rate of 77% in their elections during the first six months of 2022, according to Bloomberg Law, and they organized more workers during that period than they did over the same period of 2021.

“The unions have won against all odds—we’ve never had them win against these superstar corporations before” says John Logan, a professor of labor history at San Francisco State University. “That’s really a unique achievement in U.S. labor history.”

Some of the union activity has occurred at big companies that once seemed immune from organizing drives, like Starbucks, Amazon and Apple. Workers at an Apple store in Maryland voted to unionize in June and Apple workers in an Oklahoma store will vote on union representation in October.

Read More: U.S. Workers Are Realizing It’s the Perfect Time to Go On Strike

While the successful labor drives of the past year have caught public attention, unionization rates in the U.S. are still much lower than they were half a century ago. Just 6% of the private sector workforce belongs to unions today, even though approval of labor unions in the U.S. is at 71%, according to a Gallup poll, the highest approval rate since 1965. And as recession fears loom, there’s also the possibility of employers making layoffs, further weakening workers’ leverage.

Employers argue that unions are overplaying their strength; in 2021, unions sought to represent just 46,880 of the roughly 103 million eligible private sector workers in the country, according to Congressional testimony in September by G. Roger King, a longtime labor lawyer who now works at the HR Policy Association. Despite the perceived success of Starbucks Workers United, only a fraction of a percent—0.75%—of all Starbucks in the U.S. locations have been organized, he says.

Anti-union campaigns and employee surveillance

Unionization rates may be low in part because employers have a variety of tools at their disposal to push back against unions, and they haven’t hesitated to use them, knowing that usually the penalties issued by the NLRB for violating labor law amount to a slap on the wrist, says Kate Bronfenbrenner, director of labor education research at the ILR School at Cornell University.

“The majority of workers have made clear that they would prefer to be represented by a union,” Bronfenbrenner says. “But that desire is thwarted by a combination of weak labor laws and aggressive employer anti-union campaigns—replete with threats, interrogation, surveillance, discharges, harassment, discrimination, and bribes.”

Bronfenbrenner analyzed a random sample of 286 NLRB elections between January 2016 and June 2021 and found that three-quarters of employers brought in one or more management consultants to run an anti-union campaign, 45% threatened workers with plant closings or outsourcing, and 49% made promises of improvement in return for workers not supporting the union.

Technology has allowed employers to get more sophisticated, she found. Employers used surveillance—including social media, cameras, and GPS devices—in nearly one-third of all workplaces where union elections were held, up from 14% in the early 2000s, her research found.

Broadly, the National Labor Relations Act prohibits employers from spying on union gatherings, granting wage increases that are timed to discourage employees from forming a union, and threatening to close a plant if workers organize a union.

Read More: What to Do if You Think Your Boss Is Trying to ‘Quietly Fire’ You

Some complaints filed with the NLRB show just how high tensions are running between employers and employees in a time of more organizing.

One such complaint, which is still being litigated, relates to a Michigan nursing home. According to NLRB filings by an employee union, Notting Hill of West Bloomfield hired a security guard to patrol its parking lot in the weeks leading up to an election in which the nursing home was trying to decertify the union, SEIU Healthcare Michigan. Notting Hill said in its response to the filing that it had hired security because union officials ignored an administrator’s request to only meet workers at an agreed-upon spot outside the facility. The union alleges that the security officer used his SUV to block union officials from talking to workers. Notting Hill alleges in filings that the union responded by picketing the facility, and an NLRB judge later said that picketing was illegal. The election took place in August 2021 and the results favored the union, but Notting Hill is arguing, in court filings, that the union unfairly swayed the election by picketing, and that the NLRB, which oversees union elections, did not provide ballots in other languages for workers who needed them.

Anissa Keane, an employee trying to organize workers at a cannabis dispensary in Arizona owned by the company Curaleaf, alleged in NLRB filings that the company told employees that they’d lose their tips if they organized. She also alleged that the company told workers that union representatives would come to their houses without permission to “force” them to sign union cards. Keane had suggested that the union would ask for COVID-19 hazard pay and a raise for workers, she says; in NLRB filings, she alleged that in response, the company offered workers “better discounts” on marijuana. Less than a month after the company learned that the employee was trying to organize the workplace, it fired her, Keane says, telling her she violated the cash handling policy; she says it was her first violation, and that a supervisor had told her workers only get terminated after four cash handling violations.

(Curaleaf argued, in court filings, that Keane was fired because she had three write-ups. A NLRB judge ordered Curaleaf to pay her back pay and offer her former job back. In a statement provided to TIME, Curaleaf said that Keane was not terminated for her union activity and that it is appealing the NLRB decision.) “We are committed to providing a positive corporate culture where everyone is treated with respect and dignity,” the statement said. “We respect the right of Team Members to decide if union representation is in their best interest and we believe in educating Team Members on what it means to be represented by a union.”

When the Culinary Workers Union tried to organize the Red Rock Casino Resort Spa in Nevada, casino executives allegedly ordered supervisors to prepare a “MUD list” to indicate which employees were pro-management (M), pro-union (U), or don’t know (D), and threatened workers with the loss of benefits if they supported a union, according to the administrative law judge’s decision. The judge found that the casino committed 20 unfair labor practices before the union election, including serving branded “VOTE NO” steaks to employees in advance of the union vote, and assigning a worker who served on the union committee since 2009 to clean floor drains even though she had been placed on “light duty” assignment after an injury. The judge found that Red Rock engaged in unfair labor practices and ordered the company to cease and desist from threatening employees with reprisals if they select union representation. Red Rock appealed the decision and the case is still open.

In court filings, the company argues that it gave its workers much-needed benefits to improve conditions, and that any layoffs it may have made in 2020 were a response to COVID-19, not union organizing. The company declined to comment on record for this story

Starbucks allegedly fired seven workers—described by unions as “The Memphis Seven”—who were involved with labor organizing in Tennessee, according to an injunction filed by a NLRB regional director in U.S. District Court, the court ordered Starbucks to reinstate the workers. The workers, represented by Starbucks Workers United, also alleged that managers of the Memphis store took down pro-union postings supplied by community members and opened the store as drive-thru only due to “short-staffing” on days the union had planned to host a sit-in, lessening the campaign’s impact. Starbucks said in a statement in September that it was appealing the order to reinstate the workers because those workers had “violated numerous policies” and failed to maintain a secure work environment. The ruling “sets a worrisome precedent for employers everywhere who need to be able to make personnel decisions based on their established policies and protocols,” the company said at the time. Starbucks also added, in a separate statement provided to TIME, that it respects its workers’ rights to organize. But “from the beginning, we’ve been clear in our belief that we are better together as partners, without a union between us, and that conviction has not changed,” the company said.

Lawyers for employers—and the Wall Street Journal Editorial Board— argue that the NLRB is biased under the Biden Administration. Some employers have alleged, in NLRB filings, that the board is trying to change labor law in its decisions. The NLRB uses cases as “a mere jumping-off point to enable discussions of the issues it wants to address and the precedents it wants to overrule,” Red Rock Casino argued in a NLRB filing. In August, Starbucks accused NLRB officials of “systemic misconduct” for working with the union during a recent election and asked the agency to suspend all Starbucks mail-ballots nationwide. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce followed up in September with a letter to the Inspector General of the NLRB, David P. Barry, asking him to investigate allegations that NLRB staff were showing favoritism towards workers who support unionization, saying that other businesses had also raised concerns about NLRB staff conduct. “For Americans to have confidence in our government institutions, they must be seen as operating fairly,” Neil L. Bradley, the Chamber’s executive vice president, wrote in the letter. The NLRB said, in a public comment released in response to the Starbucks letter, that it does not comment on open cases, but that the agency has “well-established processes” that allow parties to raise challenges about elections, and that companies should raise their challenges through specific filings. “ The regional staff – and, ultimately, the Board – will carefully and objectively consider any challenges raised through these established channels,” the agency said.

Companies say that they have a right to tell workers about the potential downsides of joining a union, just as unions can talk about the upside. Just how aggressive employers can be in educating workers is the subject of many NLRB disputes, but sometimes it can result in labor organizing efforts collapsing.

When employers aggressively oppose a union drive, win rates are 10% to 40% lower than in elections in which employers take no action, according to Bronfenbrenner’s research.

Few repercussions for employers

The consequences for skirting the law are minimal—in many cases, an NLRB judge will only order an employer to cease and desist any unfair labor practices. Sometimes employers will be required to offer terminated employees their jobs back and reimburse them for back pay or job search expenses. The NLRB can seek temporary injunctions against employers or unions in federal courts, and the courts can order parties to pay a fee, but even those fees are minimal. In June, a district court ordered a New Jersey hotel to pay $10,000, as well as NLRB attorney fees, after it found that the hotel had failed to comply with its prior temporary injunction.

Many employers know that even if they lose their case with the NLRB, they’ll have intimidated workers and subsided a union drive, says Robert Anthony Bruno, director of the Labor Education Program at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

Bronfenbrenner says that the NLRB does not have the funding or enforcement powers it needs to deal with the influx of petitions, elections and complaints it receives. The agency has received the same Congressional funding of $274.2 million for nine straight years, it said in a press release on Oct. 6. Adjusted for inflation, the NLRB’s budget has fallen 25% since 2014. In the last two decades, the agency’s staffing has dropped 39%.

Read More: Facebook Faces New Lawsuit Alleging Human Trafficking and Union-Busting in Kenya

Bronfenbrenner has urged Congress to pass the PRO Act, which, among other things, would allow workers the option of bringing their cases in federal court, and which would prohibit so-called “captive audience” meetings, in which employers require workers to attend meetings about the downsides of joining a union. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce says that the PRO Act would harm workers, employers, and the larger economy.

Even if labor law relating to how elections are held does change, the unions that have organized over the last year will face another obstacle.

Employers can engage in what Bruno calls a “soft” form of resistance: dragging their feet on negotiating a contract. If a union and employer don’t have a contract a year after an election has been held, the company stands a chance of getting the union decertified before it ever gets a contract, he says, erasing the hard-fought battles that led to unionization in the first place.

That’s an obstacle Starbucks workers say they are facing. Although the first of the 240 stores organized in the last year voted for a union in December, none of the stores have a contract yet. (Starbucks said in late September that it had sent letters to 234 stores asking the union to join it at the table and offering a three-week window in October for bargaining.)

While some employers have managed to quell labor action, for others, failing to reach an agreement on a contract, may simply mean more unrest down the road. In the case of Starbucks workers they’re not giving up: unions in Atlanta and Maine held strikes in September over issues including their lack of a contract.

- Tarana Burke: What 'Me Too' Made Possible

- Column: Youth Incarceration Harms America's Children. It's Time to End It

- What TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders Can Teach Us

- 14 Actually Good Books To Teach Kids About Climate Change

- Column: The Fate of the Amazon Rainforest Depends on the Brazil Election

- Lessons From a Half-Century of Reporting on Race in America

- What Happens If I Get COVID-19 and the Flu at the Same Time?

- A Year After Striketober, Employers and Labor Unions Aren't Getting Along